Impact of the Inuit Arts economy

This report was prepared for Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada by Big River Analytics. It does not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Government of Canada. For a copy of the full report, please contact andree.lacasse@rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca.

Executive summary

Contemporary Inuit arts and crafts as they exist today draw on culture and traditions that long predate settlers’ arrival in the Arctic. However, some of the production methods, distribution channels, marketing, and the place of this art among other contemporary forms of fine art can be traced to the late 1940’s when James Houston visited the Canadian Arctic. Houston’s enthusiastic response to the caliber and beauty of the art he saw in the North resonates to this day. In the less than 70 years since the commercialization of Inuit art began, the production of Inuit arts and crafts has spread across Inuit Nunangat and outside Inuit Nunangat and has found an enthusiastic market across Canada and around the world. In 2015 the Inuit visual arts and crafts economy in Canada contributed over $64 million to Canadian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and it accounts for over 2,100 full time equivalent jobs.

The production of Inuit arts and crafts is remarkably widespread with an estimated 13,650 Inuit artists producing visual arts and crafts in Canada. This total comprises 4,230 artists producing works with the objective of earning income and 9,420 who produce for their own use or for the use of their family, friends, or community. Footnote1 The total Inuit population aged 15 years and older in Canada, based on the 2012 Aboriginal Peoples Survey, is 52,980. This implies that 26 percent of the Inuit population aged 15 years and older is engaged in the production of visual arts and crafts. This level of participation, including the artistic contributions of 9,420 individuals whose artistic objectives do not include earning money, is indicative of the continued importance of art in Inuit culture today.

In 2015, Inuit artists producing visual arts and crafts for income earned over $33 million net of all costs, and through their purchases of inputs and the expenditure of their earned income they generated an additional $12.5 million in spin-off impacts. Over the same time period, Inuit artists producing visual arts and crafts for consumption, through their purchase of inputs, generated $17 million in economic activity.

In 2015, Inuit working in performing arts or related occupations contributed $13.4 million to GDP in Canada. The economic activity generated by these performing artists and creative workers created or supported 419 full time equivalent jobs. In the related industries of film, media, writing and publishing, Inuit artists and creative workers contributed $9.8 million to GDP in Canada. The resulting economic activity created or supported an additional 208 full time equivalent jobs.

In 2015 the Inuit arts economy contributed $87.2 million to Canadian GDP. The economic activity attributable to Inuit arts created or sustained over 2,700 full time equivalent jobs in Canada, with the vast majority held by individuals across Inuit Nunangat.

For those unfamiliar with economic impact assessments, the first section of the Technical Appendix included at the end of this report provides a brief description of some of the topics and concepts frequently used throughout this report.

Distribution of visual artists

Visual artists are distributed across Inuit Nunangat the rest of Canada in different concentrations. Table 1 presents the distribution of artists in each region of Inuit Nunangat and outside Inuit Nunangat. Artists producing works for income are most highly concentrated in Nunatsiavut (11 percent), and least concentrated outside Inuit Nunangat (4 percent). Artists producing works for consumption are most highly concentrated in Nunavut (23 percent) and least concentrated outside Inuit Nunangat (12 percent). Overall, the concentration of artists is highest in Nunavut (33 percent) and lowest outside Inuit Nunangat (15 percent).

Economic impact

The economic impact in this report is measured in terms of GDP. Loosely, GDP in this context measures the final value of the goods and services produced in the Inuit arts and crafts economy, from hunters on the land catching animals for inputs into the production of arts and crafts to artists producing and selling their wares and finally to artists and producers of inputs purchasing goods and services in their community with their earnings. Using GDP to measure economic impact helps avoid double counting the components of the Inuit arts economy. The total economic impact comprises three components: the direct component, which is largely payments to artists net of expenditures, the indirect component, which captures the demand created by artists for inputs into their production, and the induced component, which measures the spillover impact when industry participants spend the money they have earned in the local economy.

Table 2 shows the total economic impact of visual arts and crafts in terms of GDP by region, component, and artistic production type (income or consumption).

Secondary sales

The casual reselling of Inuit arts and crafts does not represent significant new economic activity. However, the large-scale auctioning of many pieces conducted by auction houses does generate an economic impact through the work of curating, photography, design, the production of catalogues, restoration, the building of bases, insurance, marketing, and the storing of artistic pieces. Two auction houses dominate the secondary sales of Inuit art in Canada: Walker’s Fine Art and Estate Auctions, and Waddington’s Auctioneers and Appraisers. Based on publicly available data on realized prices at auction and the costs associated with buying and selling Inuit art at both Walker’s and Waddington’s, the economic impact of the secondary sale of Inuit art at auction is included in our analysis and it is presented in the second-from-bottom row in Table 2.

Impact by region

The total economic impact of the visual arts and crafts economy in Nunavut was $37.3 million in 2015. This estimate comprises the total contribution from artists producing for income ($27.6 million), and those producing for consumption ($9.7 million). This total is not directly comparable to previous estimates of the economic impact of Nunavut’s arts and crafts sector because no prior study included the impact associated with the production of arts and crafts for consumption. A more comparable estimate, the impact originating with artists producing for income, shows a decline of 9 percent since 2013 (Nordicity Group and Uqsiq Communications Ltd., 2014), though this measured decline is largely a function of methodological differences in the calculation of the indirect impact. Direct and induced component estimates, which are generated using similar methodological approaches but entirely different data sources, show a slight decline between and 2013 and 2015. This suggests that, after accounting for methodological differences, a significant decrease in wholesale activity has been mitigated by an increase in direct-to-consumer Footnote2 (primarily online) sales.

For the remaining regions of Inuit Nunangat and outside Inuit Nunangat, our estimates serve as the baseline measure of the total economic impact of the Inuit arts and crafts economy because there has been no formal assessment of the economic impact of Inuit arts and crafts in any region outside Nunavut.

In Nunavik, the total economic impact of Inuit arts and crafts in 2015 totals $11 million. This estimate comprises $7.9 million from the activities of artists producing for income and $3.1 million from the activities of artists producing for consumption.

In Nunatsiavut, the total economic impact of Inuit arts and crafts in 2015 totals $2.9 million. This estimate comprises $2.3 million originating with the activities of artists producing for income and $0.6 million originating with the activities of artists producing for consumption. Relative to other regions in Inuit Nunangat, the economic impact in Nunatsiavut comes disproportionately from artists producing for income.

In the Inuvialuit Region, the total economic impact of Inuit arts and crafts in 2015 totals $3.2 million. This estimate comprises $2.4 million originating with the activities of artists producing for income and $0.9 million originating with the activities of artists producing for consumption.

Outside Inuit Nunangat, the 2015 total economic impact of Inuit arts and crafts in 2015 totals $9.6 million. This estimate comprises $5.5 million originating with the activities of artists producing for income, $2.8 million originating with the activities of artists producing for consumption, and an additional $1.4 million attributed to the activities of the secondary sales of Inuit art at auction in Ontario.

Distribution channels

There are three primary distribution channels used to bring Inuit art to market: direct-to-consumer, retailers, and wholesalers. Direct-to-consumer sales (primarily online) are of increasing importance in all regions and the growth in this distribution channel offsets some of the decline in retail and wholesale channels.

Table 3 outlines the direct impact in terms of payments to artists net of their expenditures from each distribution channel.

Overall, 67 percent of the direct impact originates with direct-to-consumer sales. Artists earn $22.1 million net of their expenses through direct-to-consumer sales. Online sales networks, primarily local Facebook buy/sell groups and the 26,300 member "Iqaluit Auction Bids" have increased the importance of the direct-to-consumer distribution channel for artists.

Retail sales accounts for 18 percent of net payments to artists and wholesale accounts for the remaining 15 percent of the direct impact. The wholesale channel is likely to have a diminished importance in 2016 relative to 2015 because a major wholesaler ceased operations at the end of 2015.

The importance of each distribution channel varies by region. For example, in Nunavut wholesale sales account for 20 percent of the direct impact while wholesale sales in other regions do not exceed 6 percent of total direct impact. The importance of wholesale sales in Nunavut can be attributed to well-established oranizations such as Nunavut Development Corporation. Retail is particularly important for the Inuvialuit Region, with 27 percent of the direct impact originating with retail sales whereas other regions’ retail components do not exceed 20 percent.

While artists in all regions rely primarily on direct-to-consumer sales, artists in Nunavik and outside Inuit Nunangat rely on direct-to-consumer sales for 79 percent and 80 percent of their total net payments to artists respectively.

Artist income and employment

Income

Visual arts and crafts are labour intensive. Artists spend many hours creating each unique piece of work. Unlike a recording artist or author whose creation can be replicated and sold many times at a low marginal cost, artists producing visual arts and crafts, apart from some printmakers, invest their time and are paid once for each piece of art they produce. In addition, each piece of art requires expensive inputs, and this further affects the profitability of visual arts and crafts. As a result, Inuit artists producing visual arts and crafts, on average, earn only $12.17 per hour net of their expenses. Artists’ incomes and hourly earnings from art are widely dispersed as would be expected in an industry where some artists produce one or two items for sale per year, and others work full-time on their craft.

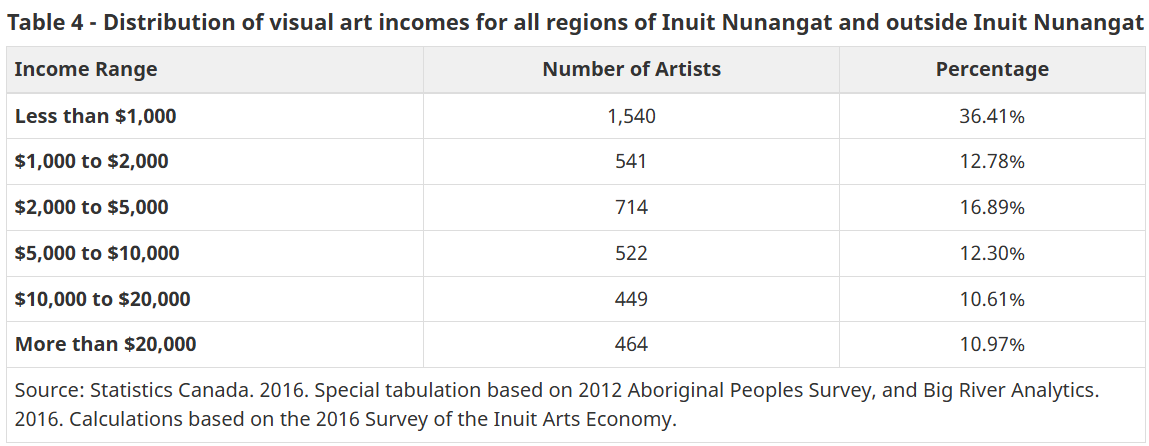

To estimate the average income earned from art by Inuit artists, we estimate a distribution of annual income earned by Inuit artists from their arts activities. This distribution also allows us to estimate the number and proportion of artists earning incomes in various ranges (Table 4). The estimated income distribution is highly skewed, with the estimated median annual income from art activity at $2,089, while the mean art income is $7,810.

The skewed income distribution is consistent with a large number of artists making relatively small incomes from art as a supplemental form of income and a smaller number earning large incomes as a full-time endeavor. Further evidence for this can be seen in the percentages of artists in low art-income ranges compared to the percentage in high art-income ranges, as seen in Table 4. Just under half of artists (2,081) earned less than $2,000 from their art activities in 2015, but 22 percent (913) earned $10,000 or more from art activities in 2015.

Even when it is not an artist's main source of income, income from art is important. Table 5 shows the average total income for artists Footnote3 in each region, compared to the average total income for non-artists, and the difference between the two. Except for in Nunavik, artists generally earn significantly less than their non-artist counterparts.

On average, artists producing art for income earn 31 percent of their total income from art, though the proportion of total earned income from art is likely even higher. For many artists, that supplemental income is critical to their own and their family's well-being.

Because Inuit artists have relatively low incomes, each additional dollar earned from their art is especially valuable. For Inuit artists living in the North, the problem is exacerbated by the high cost of living. Food can be up to three times as expensive as in the south (Nunavut Bureau of Statistics, 2015) and decent housing is out of reach for many.

Artist income and production type by gender (visual arts and crafts)

Average artist incomes by gender

Table 6 presents average artist incomes by gender, from direct distribution channels and all distribution channels. On average, males earn about 50 percent more per year from direct channel sales than females ($6,466 for males compared to $4,380 for females). When adding retail and wholesale channels, this discrepancy grows markedly, so that males earn more than twice what females earn on average from all distribution channels ($11,625 for males compared to $5,195 for females).

The discrepancy in earnings by gender is large enough that males account for 61 percent of the estimated direct economic impact from art activities, despite representing just 41 percent of the artists earning income from art. The difference in earnings by gender is even greater when looking at retail and wholesale channels. Males earn 81 percent of the artist income from retail and wholesale channels, $8.9 million in total compared to $2.0 million for women.

Product types by gender

The large differences in male and female art incomes can be explained by examining the types of art that each gender engages in. Table 7 compares the proportion of artist incomes in direct distribution channels to the proportion of retail and wholesale sales by product type. Males and females produced significantly different product mixes, especially when it comes to carvings and sewn goods. Men reported earning 56 percent of their earnings, on average, from carvings, while women reported earning just 4 percent from carvings. On the other hand, females earned 57 percent of their earnings from clothing and other sewn goods, compared to 3 percent for males. However, males and females earned roughly the same proportions of their earnings from jewellery and other product types.

Comparing the product mixes by gender to the product mix for retailers and wholesalers helps explain why men tend to earn so much more than women do. Men account for the vast majority of carvings, which represented three quarters of retail and wholesale sales. The same is true for print graphics, the other major retail and wholesale product category, although to a lesser extent. Conversely, although women produced the vast majority of sewn goods, these only accounted for 7 percent of retail and wholesale sales.

Employment

The production and sale of Inuit arts and crafts produces substantial employment in each region of Inuit Nunangat and outside Inuit Nunangat. Table 8 provides an overview of employment attributable to the production and sale of Inuit arts and crafts. Employment is broken down into the constituent components of the industry: the direct, indirect, and induced components representing different employment types and full-time equivalent costs.

Collectively, the production and sale of Inuit arts and crafts creates or supports 2,129 full time equivalent jobs (FTEs). A majority of those jobs (1,150) are in Nunavut. The vast majority of FTEs (1,423 or 67 percent) are attributable to the direct impact - payments to artists net of expenses. While there are many more than 1,423 artists producing for income, if we account for the part-time nature of the work for many artists, the measure of full time equivalent work is 1,423 jobs.

The indirect component of the Inuit arts economy consists of payments for inputs into the artistic process, including retail and wholesale margins. Retail and wholesale activities are inputs into the production process, even though they provide services after the creation of the art, because they contribute to the value of the product at the point of purchase. The indirect component contributes 462 FTEs nationwide. A substantial proportion of the indirect FTEs is attributable to the large number of artists producing works for consumption. While they tend to produce fewer pieces and spend fewer hours per week working on their artistic projects, the 9,420 individuals (70 percent of all artists) producing arts and crafts for consumption contribute to the Inuit arts economy through the demand they create for artistic inputs and the spinoff impact that results from that expenditure.

Finally, the induced component, which includes the spinoff impact related to the expenditure of income earned in the direct and indirect components of the Inuit arts economy, contributes 244 FTEs. These positions are concentrated in retail and service sectors and as a result, the FTE cost tends to be lower than for those attached to the indirect component of the arts economy, which are more concentrated in extractive industries.

Social media sales

In October 2010, Facebook introduced "Groups", pages that can be created by individuals related to a particular topic. Groups allow Facebook users to exchange ideas, photos, videos, questions, notices, and other content related to the group topic. Soon after the introduction of Facebook Groups, community Groups became a forum for the local exchange of information and as a platform for Facebook users to remain connected to a community regardless of their geographic location. Groups specializing in news and current events, buy/sell, recreation, and community bulletins Footnote4 appeared for most communities, North and South alike.

The change to Groups that took place in February 2015 facilitated and formalized the sale of goods and services and it has increased the effectiveness of these Groups as a sales platform. Some Groups specializing in the sale of arts and crafts have mushroomed into large networks facilitating the sale of a significant amount of Inuit arts and crafts. The best example is "Iqaluit Auction Bids" (IAB), which was founded by David Alexander in November 2011. By March 2012, the group had over 7,500 members. At the time of writing, IAB membership is at over 26,300, a growth of over 300 percent since 2012. The description of IAB reads "Homemade products, arts, crafts and the tools to make the product(s) are all welcome to this site, please no more store bought items such as footwear (shoes, boots, clothing, nose studs and so on), non-homemade items will be removed without notice." IAB is an active grassroots marketplace for visual arts and crafts in the North with an increasing number of buyers and sellers from the South. Artists who participated in our information sessions mentioned the effectiveness of the platform for selling their works and their surprise at the prices they are able to receive. Part of the success of IAB and similar groups is attributable to the connection consumers feel to the artist. Consumers are glad the money is going directly to the producer instead of supporting a long supply chain: "The prices are good. I noticed the kamiks [sic] — they run fairly high, but when you're buying direct from the people making them, it's worth it, to support them" said Liz Fullenwider, IAB customer (CBC News, 2012).

IAB and local buy/sell Facebook pages have created a direct-to-consumer (online) distribution channel at a scale that is new in the Inuit arts economy. Due to the seasonality of sales (higher in winter and lower in summer) this study was unable to measure the impact of Facebook online sales directly, however, statements by participants of the information sessions held across Inuit Nunangat indicate the rise of online sales is driving the increased importance of the direct-to-consumer distribution channel.

Igloo Tag

The Government of Canada is transitioning the Igloo Tag to the Inuit Art Foundation (IAF). This transition provides an opportunity to review the Igloo Tag critically, and it provides a window for change and improvement.

In the 2016 Survey of the Inuit Arts Economy undertaken to inform this project, retailers, wholesalers, and consumers were asked how much they value the presence of an Igloo Tag when considering the purchase or sale of a piece of Inuit art. Interestingly, retailers and wholesalers Footnote5 assign a relatively low average value to the Igloo Tag ($7.27) whereas consumers assign a much higher average value to the Igloo Tag ($117.23). Table 9 presents these estimates with their associated standard errors and a 95 percent confidence interval. Footnote6

There are six licensees issuing approximately 30,000 Igloo Tags annually. An average consumer value of $117.26 implies an annual aggregate value to consumers of just over $3.5 million dollars. The cost of maintaining the Igloo Tag, including database maintenance, printing, and marketing, is around $100,000 annually, so the net value conferred by the Igloo Tag is significant.

Performing arts

Because of data limitations, we narrow our examination of the economic impact of Inuit performing artists and related creative occupations to those who earn income from their craft. Because we have included creative occupations in the performing arts calculations, it is likely that there is some overlap between the performing arts estimates and film, media, writing and publishing. Payments to artists net of expenditures (direct impact) total $8.4 million. In performing arts, the indirect impact comes from activities such as venue rentals, equipment, instruments, retail sale of tickets, and recordings, and these total $3.0 million. Induced impact contributed just over $1.9 million. The total economic impact in terms of GDP was just under $13.4 million in 2015.

Employment impact

Table 11 provides an overview of the estimated FTE costs for direct, indirect, and induced components of the economic impact. We estimate 495 FTE jobs were created or sustained by Inuit performing arts and performing arts-related occupations in 2015.

While the employment impact of Inuit performing arts in Canada is significantly smaller than, for example, visual arts and crafts, this is partly attributable to the higher direct FTE cost in the performing arts sector. Full time performing artists tend to earn more than full-time visual artists.

Film, media, writing and publishing

Film, media, writing and publishing vary significantly between Nunavut and the other respective regions in Inuit Nunangat. In Nunavut, the film and media production industry is significantly more developed, and the size of the industry is much larger.

As a category, film, media, writing and publishing are considered together because the regional media production companies in the regions of Inuit Nunangat are largely representative of most of the film, media, writing and publishing that takes place within the region. The regional media production companies include:

The Inuit Broadcasting Corporation (IBC) in Nunavut;

The Inuvialuit Communications Society (ICS) in the Inuvialuit Region;

Taqramiut Nipingat Incorporated (TNI) in Nunavik; and

The OKâlaKatiget Society (OK Society) in Nunatsiavut.

Each of these companies produces local film and media content and both Avataq (parent organization to TNI) and ICS engage in print media. With the exception of TNI Footnote7 , we include estimates of the economic impact of all of these production companies.

For Nunavut, we have expanded the data collection effort to include all the production activity that took place in 2015, though we have included a second estimate to ensure comparability with other regions. , media, writing and publishing given the transferability of skills required in performing arts and related creative jobs and the required skills to work in film, media, writing, and publishing.

Table 12 provides a breakdown of the total economic impact of film, media, writing and publishing in each region of Inuit Nunangat and outside Inuit Nunangat. There is likely some overlap between performing arts and film, media, writing and publishing given the transferability of skills required in performing arts and related creative jobs and the required skills to work in film, media, writing, and publishing.

Just under $10 million in terms of GDP was generated in 2015 by Inuit film, media, writing and publishing. This does not include economic activity that took place in Nunavik. Inuit film, media, writing and publishing supported 208 FTE jobs in Canada in 2015.

Total economic impact

Table 13 details the total economic impact of the Inuit arts economy in Canada. The Inuit arts economy in Canada contributed $87.2 million in 2015. This total consists of $64 million from visual arts and crafts, $13 million from performing arts, and $9.8 million from film, media, writing and publishing.

Table 14 provides the total estimates of FTE jobs created or sustained as a result of the Inuit arts economy in Canada in 2015. 2,704 FTE jobs, comprised of 2,106 in visual arts and crafts, 419 in performing arts, and 208 in film, media, writing and television were created or sustained in 2015 as a result of economic activity generated by Inuit art.

Footnotes

Footnote 1

In this report, artists producing for their own use, the use of their family, friends or community are said to be producing for "consumption" as opposed to "income".

Footnote 2

The direct-to-consumer distribution channel refers to both online and in-person sales unless otherwise noted.

Footnote 3

Income from all sources including art, employment and transfers.

Footnote 4

For example, Igloolik, NU has the following Facebook Groups: Igloolik Sell/Swap (5,298 members), Igloolik (693 members), Igloolik Auction Bids (605 members), and Igloolik Carvings (413 members). In 2011, the population of Igloolik was 1,454 (NHS Statistics Canada, 2011).

Footnote 5

In terms of qualitative comments, retailers suggested there was little value to the Igloo Tag whereas wholesalers, while reporting a relatively low monetary value described the Igloo Tag in favourable terms.

Footnote 6

Readers will notice that not all estimates are presented with confidence intervals. Only estimates derived from a single data source are able to be presented with confidence intervals.

Footnote 7

TNI was unable to supply the required inputs by the time of writing.

Footnote 8

TNI is the only film, media, writing and publishing organization in Nunavik. A description of their activities is available in Nunavik’s regional analysis, however not quantitative estimates were possible.

Footnote 9

TNI was unable to supply the required inputs by the time of writing.

Footnote 10

While no economic impact was estimated for Nunavik film, media, writing and publishing, TNI employs between 12-15 workers, and additional workers at Avataq would increase that number. We include 15 as a conservative estimate.